The healthcare reform bill has avoided failure, and gained Royal Assent on 27 March this year. In its wake lie the structural reconfigurations around strategic health authority (SHA) and primary care trust (PCT) clusters that have already commenced as part of the 2012 Operating Framework plans and the creation of commissioning support services. However, as Paul Fitzsimmons, managing director of MedeAnalytics, discusses, the NHS is now in danger of suffering from temporary paralysis.

During a transition period in which PCT management has been aggregated upwards and become more detached from previously-localised responsibility, there has been no handover to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) as they remain in shadow form.

The infrastructure for monitoring progress of QIPP savings, which used to span from SHAs to general practices, has been dismantled, leaving managers at all levels in the new hierarchy flying blind for the foreseeable future at a time when direct line of sight on performance transparency is most needed

Additionally, the infrastructure for monitoring progress of QIPP savings, or the ‘Nicholson challenge’, which used to span from SHAs to general practices, has been dismantled, leaving managers at all levels in the new hierarchy flying blind for the foreseeable future at a time when direct line of sight on performance transparency is most needed.

Once the newly-forming commissioning support units/organisations (CSSs) come online, some form of performance visibility will emerge again. But that is likely to take several months and will only start once CSUs are fully established and won’t address the full NHS hierarchy, as they will only be concerned with their CCGs.

What is urgently needed is a way to get to grips with the unwarranted variations that persist but go unnoticed because they are masked by the way data is aggregated.

Inappropriate admissions

A prime example can be found in management of inappropriate hospital admissions related to long-term conditions, diabetes in particular. These are admissions for which the primary diagnosis, i.e. the condition for which the patient was hospitalised, would not normally justify an admission. In some of these instances, it may turn out that the admission was in fact appropriate, but experience shows that the vast majority are cases that should have been treated outside an acute hospital setting.

The NHS as a whole should be concerned because these represent a significant share of the overall inappropriate admissions annually and have already cost the NHS in excess of £15m over the first three quarters of the current financial year alone. For example, in the NHS London strategic health authority cluster, in 2011/12 29% of inappropriate hospital admissions were due to diabetes. The total cost of this amounts to £2.8m.

What is urgently needed is a way to get to grips with the unwarranted variations that persist but go unnoticed because they are masked by the way data is aggregated

The challenges in tackling this come from the current difficulty in accessing the existing data which can reveal where problems arise, together with the lack of dedicated staff who can work with stakeholders to take action to resolve the problem.

On the question of access to the data, as SHAs and PCTs have begun to cluster, the problem of integrating reporting systems to provide relevant views has not been a priority. This means that although the data exists, not enough effort has gone into converting it into meaningful information.

The rate of inappropriate inpatient admissions associated with diabetes illustrates the difficulties. Overall, the figures show reasonable stability across the board through time and, in particular, for the NHS North of England, which has stayed at around 44%.

Regional variations

The apparent stability in the North covers substantial variation between the different PCTs across the old SHAs. The aggregate level, suggesting steady figures at around 44%, disguises wide differences in performance between the component organisations.

The figures contain both good and bad news. There have been significant gains in several clusters, but NHS South Yorkshire’s position has deteriorated dramatically from 39.7% to 48.4%. NHS Humber, conversely, shows what can be achieved - that a target level of 32% is attainable.

The next stage is to drill down further into the data. Values for individual PCTs again show more variation locally. In particular, several PCTs show significant deterioration over a two-year period.

As SHAs and PCTs have begun to cluster, the problem of integrating reporting systems to provide relevant views has not been a priority. This means that although the data exists, not enough effort has gone into converting it into meaningful information

This is not just a northern phenomenon, though. The same situation can be found across PCTs in other regions.

Management has been moved upwards into clustered organisations but, as the examples above show, it is not enough to view data at that level, because it tends to average out serious levels of variability at local level, disguising variations from managers.

Addressing variations

To address the problem of unwarranted variation, PCTs and their successors need access to information on which they can base effective action and they need staff with the skills and the confidence to use it to drive discussions with providers and GP practices around changing their behaviours.

As SHAs and PCTs have begun to cluster, the problem of integrating reporting systems to provide relevant views has not been a priority. This means that although the data exists, not enough effort has gone into converting it into meaningful information

Consolidation of PCTs into clusters, the delay in legislation around establishing CCGs, and the current uncertainty around future commissioning support has left a void in local engagement with providers and GP practices. This is having a direct impact on achieving the potential savings required by the QIPP programme.

Returning to the example of inappropriate admissions associated with diabetes and looking at sample PCTs from each of the four SHA clusters, the extent to which these patients are triggering unwarranted escalation of care and cost is immediately clear.

Figure 1 demonstrates the degree to which simple diabetic patients with no complications across a PCT patch are admitted into hospital only to be discharged without having any procedure. This may indicate an unwarranted escalation from primary care that deserves further investigation.

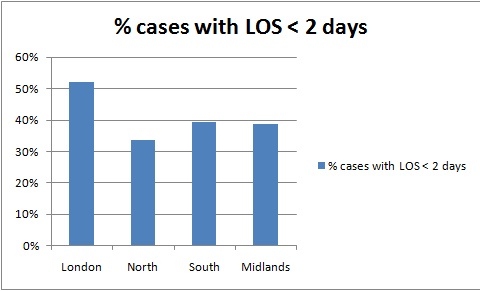

Figure 2, below, highlights turnstile treatment in secondary care in the same four SHAs, showing that a significant portion of the cases being admitted stay one day or less, which might suggest that the escalation to hospital care could have been avoided. Avoiding hospitalisation might have been significantly less costly.

Figure 2

To achieve this shift in care, PCTs and CCGs need to not only challenge acute providers to justify admissions, but also examine why their practices are failing to prevent escalation of care. This requires even more detailed data showing performance within individual practices, underpinned by individual patient records, to facilitate discussions around care plans.

The future

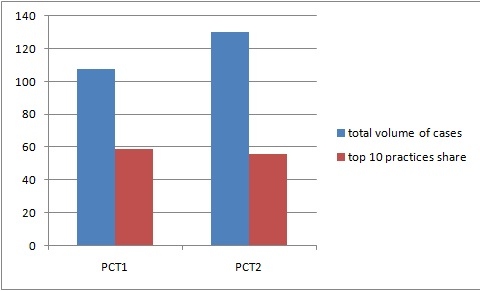

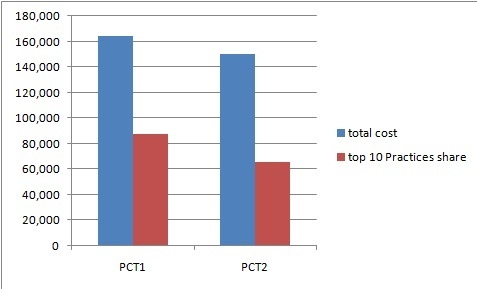

PCTs and their CCG successors must focus their efforts on the practices where intervention will generate the highest pay-off. Segmenting practices by volume and value metrics is a useful way to determine where to concentrate their initiatives. The graph below illustrates how simply this can be done showing that the top 10 in each category tend to be the same practices and usually account for the highest significant share of the patients and concentrated expenditure.

Figure 3: Volume of cases: total and top 10 GP practices

Figure 4 – Total costs and top 10 GP practices

Undertaking this work requires good analytics to support local commissioning management teams and CCGs who can harness the information and act on it.

At present there is a disconnection between what is occurring at the coalface locally and the aggregated PCT and SHA clusters currently overseeing it. This is aggravated by a lack of structured reporting and co-ordination of resources to act on it.

If not addressed quickly, this will result in a growing backlog of deferred savings having to be delivered by CCGs, even if the proposed commissioning support services are able to quickly provide them with the information they need when they are launched.