What is a TMV?

The British Standards Institute (BSI) is the UK’s National Standards Body (NSB).

It offers support to the UK Government, businesses, and industry via approved guidance known as British Standards (BS).

Following the issue of the explanatory memorandum (EM) to Building Regulations in 2009 over scald protection in areas of full body immersion (baths), it issued a revised Standard - BS EN 1111:2017 Sanitary tapware. Thermostatic mixing valves (PN 10). General technical specification

The standard offers advice on the six classification types of TMV valves:

Type 1 TMV – Single control: valves with a single control device regulating flow and temperature; (actuator movement in two planes)

Type 2 TMV – Dual control: valves with separate control devices regulating flow and temperature

Type 3 TMV – Single sequential control: valves with a single control operating through a predetermined sequence of flow and temperature. These shall have a shut-off device; (actuator movement in one plane)

Type 4 TMV – TMVs without flow control device

Type 5 TMV – Pre-set: valves not adjustable by the user of a sanitary appliance

Type 6 TMV – Other: valves with special control devices

Why are TMVs required?

The Department of Health approached manufacturers and industry for assistance in preventing or mitigating scald risk, especially in areas with vulnerable patients.

The DoH-issued publication HTM 04-01 Supplement – Performance specification D 08 thermostatic mixing valves (healthcare premises) indicates that blended water temperatures should be between 38˚C-46˚C at the point of discharge; the actual temperature depends on whether the outlet is a bidet, a shower, a handwash basin, or a bath.

These standards state: “When these devices are used to provide anti-scald protection for children, elderly, and disabled persons the mixed water temperature needs to be set at a suitable bathing temperature (body temperature approximately 38°C) as children are at risk to scalding at lower temperatures than adults.”

The Thermostatic Mixing Valve Manufacturers Association (TMVA) offered a recommended code of practice for safe water temperatures.

The D08 needs have been further supported by the testing industry developing certification to denote the valve had automatic shutoff to meet with healthcare design temperatures.

This scheme is known as the TMV3 scheme, currently run by NSF.

The EM needs highlighted, were raised by The Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH).

Best practice needs for domestic use saw similar support with the introduction of the TMV2 Scheme.

When should a TMV be used?

The Standards and guidance links all highlight the need to ensure that a risk assessment should be undertaken to identify the scald risk.

As noted, the purpose of the device is to protect the most vulnerable: children; older people; people with reduced mental capacity, mobility, or temperature sensitivity, and people who cannot react appropriately or quickly enough to prevent injury.

Building owners or landlord should discuss with designers and managers of water systems where to install any TMVs.

And the decision process should be supported by the completion of a scald risk assessment.

Those managing health services have been offered additional support within Health Service Information Sheet (HSIS) No 6, published by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), which clearly explains the risks within health and social care premises associated with hot water (bathing and showering) and hot surfaces (radiators and pipes).

Although the risk of scalding may be mitigated within this temperature range, there is a microbiological risk associated with the use of TMVs because waterborne bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Legionella propagate at temperatures between 20-45˚C.

In non-healthcare utilising a TMV in a food preparation area can accelerate biological growth during handwashing when working with poultry, fish, and raw meats.

It is therefore important that we consider ALL risks, including those which can be introduced by their use and service management.

How should TMVs be managed?

The risk assessment is a key requirement. It should not only identify the risks, but also identify the best type of valve, process, or warning (sign) to be used.

As noted, there are six TMV types, and these can be fitted with automated or manual shutoff valves and certificated to TMV2 or TMV3 by NSF, dependent on the area of use.

The assessment should also note:

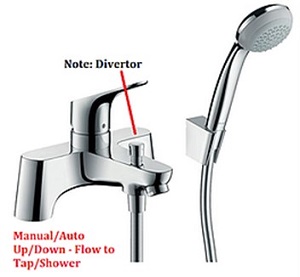

- The nominal inlet size if the valve is to be with or without a diverter

- The sanitary appliance on which it shall be used

- The type of outlet (1-6)

- The method of mounting – this should also consider backflow either as an outlet gap between the sink top and tap or in healthcare wall mounted with a measured gap from the sink top. If fitting a shower whether a single check valve on both hot and cold feeds is required

- The set point temperature that the valve is to be set i.e. dental chair or eye wash 32oC, primary school under seven, 38oC, or as noted by the operational use

- The design of the valve to meet healthcare >64oC or domestic <63o

Once fitted, the valve must be managed and maintained following the legislative needs for workplace equipment as the TMV is being utilised as a Protective Device (PPE).

The standards managing these needs note the following:

- Marking: the TMVs should be permanently and legibly marked with, the manufacturer’s or agent’s name or identification on the body or handle. The Type, flow rate, and class. Any bath/shower mixer should also indicate both flow rate classes i.e. the bath outlet (outlet 1) and the shower outlet (outlet 2)

- Identification: the temperature control device for the valve shall be identified using a scale or symbols or colours or a combination of these. TMVs should be legibly marked to indicate cold/hot inlets (under sink/concealed). Sink/basin/bath/exposed valves need only one identification of cold or hot inlet i.e. tap markings

- Inservice/cold water sudden failure tests: It is strongly advised that good PPM planning not only undertakes periodic failure and in-service testing in accordance with the set standards of those issued by the TMV schemes, but that those doing so record the seepage volumes, if any, (beyond five seconds of the test). Should the volumes be greater than 80ml then the correct action and revised PPM plan should be put in place or in the case of those valves passing volumes of >110ml that the valve is removed from service immediately

- Additional Service Needs: In the case of valves which may be subjected to biological proliferation the service needs highlighted by HSE Guidance HSG 274 part 2 should also be undertaken

What legislation should be considered?

From a health and safety perspective, it is underpinned by; the Health and Safety at Work etc Act (HSWA) 1974 (section 3 and part 3), Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (MHSWR – regulation 3) and Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations (PUWER) 1998).

Exposure either from the surface or if the aesthetics of cold water has been changed (heat it up) is covered by the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) regulations 2002.

When considering these listed areas of legislation, you should consider utilising the HSE Codes of Practice.

These approved codes are often utilised to record changes i.e. COSHH regulations 2002, ACoP L5 rev 2013. They also explain the regulatory needs.

Hot water temperatures greater than 44˚C are considered high risk with full body immersion, although showering (not full body immersion) should also be considered.

These temperatures have been associated with serious scalds and have led to fatalities, although it is stressed that a child or the elderly need far less exposure to hot temperatures.

In conclusion

In summary, TMVs should be utilised following the results of a suitable and sufficient scalding risk assessment.

The assessment should identify the valve to be installed, its type, and its design.

This will not only confirm the valve’s need, but will prevent valves from being fitted in tandem resulting in possible valve failure, the introduction of crossflow contamination, microbiological contamination, or the risk of outlet users being exposed to valve failure or poor temperature records.

The maintenance programme should be designed to ensure the valves are adequately cleaned and free from particulate matter that could inhibit the correct function of the valve and/or provide a medium for bacteria to propagate, including biofilm.

The programme should also ensure failure devices are tested and seepage results noted.

In the case of healthcare valves, those managing the system should ensure future lifecycle planning is also considered and that regular, no greater than two yearly, contact with the manufacturers is made to allow the certification needs and planning to consider if a valve is to be discontinued which could impact future spares.