The Health Services Executive (HSE) in Ireland operates approximately four million sq m of healthcare accommodation across 2,500 sites.

Of this, acute buildings account for around 1.8 million sq m, with building stock varying in age from the mid-18th Century to post 2010.

The Sláintecare Implementation Strategy identifies capital investment as a critical enabler of the reform proposed, including an increased focus on planning and management of capital development proposals.

Ellis explains: “Ireland, like so many other countries globally, is facing unprecedented challenges in the delivery of healthcare.

Post-COVID, there is a backlog of elective care, along with a growing and ageing population – and a further 20% growth expected by 2036.

“Collectively these issues are leading to increases in service demand which, alongside challenges with social care integration, and have caused a reduction in the ability to discharge, increasing lengths of stay in hospital.

Short-term funding cycles have exacerbated these issues on many hospital estates, leaving leaders with little choice but to implement infill developments which solve the most-immediate and urgent challenges, but deprive them of the opportunity to invest in longer-term programmes which address issues at the strategic level

“The net result is a population health need which cannot be easily contained, or effectively addressed, within current hospital capacity.”

Furthermore, developments in clinical delivery mean that treatment spaces now need to be bigger to accommodate more equipment and larger clinical teams, often in multi-disciplinary arrangements.

Yet the pressures of constrained capacity, ageing estates, and a lack of digital infrastructure mean clinical spaces are often not large enough, flexible enough, or fully equipped to support the demands of delivering modern care.

Then, there are the shortcomings in the quality, layout, and supporting infrastructure of clinical and supporting staff functions, many of which do not meet the expectations of today’s workforce in terms of encouraging collaboration, supporting flexible working and staff wellbeing, or providing sufficient space for research, teaching, and clinical trials.

Ellis said: “Of course, short-term funding cycles have exacerbated these issues on many hospital estates, leaving leaders with little choice but to implement infill developments which solve the most-immediate and urgent challenges, but deprive them of the opportunity to invest in longer-term programmes which address issues at the strategic level.

“And, alongside an arguable ‘health emergency’, hospital leaders are also playing their part in tackling the climate emergency.

“Carbon pledges are such that the HSE is committing to a 50% improvement in energy efficiency, which means building integration planning is needed on a system-wide, rather than individual hospital, basis.”

So, in the face of these many challenges, how can the Government adapt its approach to ensure its derives maximum value from future capital programmes of investment in Irish hospital estates?Ellis proposes a seven-point plan.

1. Programme governance and setting objectives to measure outcomes

The first step of any good project is programme planning.

This approach necessitates a clear Project initiation Document (PID) which sets out strategic project objectives and ensures alignment with national policy while enabling transparency in project planning. Such objectives typically include:

- Improving service access and minimising patient waiting – with targets set

- Creating a healing environment and promoting patient and staff wellbeing that is evidenced based

- Reducing operating costs and driving achievement of net-zero carbon, including digital technologies to reduce unnecessary travel to health facilities and CO² emissions

- Meeting requirements for modern methods of construction and incorporating room standardisation and components to unlock long-term efficiencies and flexibility

- Making systems sustainable for the longer-term workforce Centralising administration, research, and teaching for operational efficiency and flow, fabric, and footprint of digital innovation

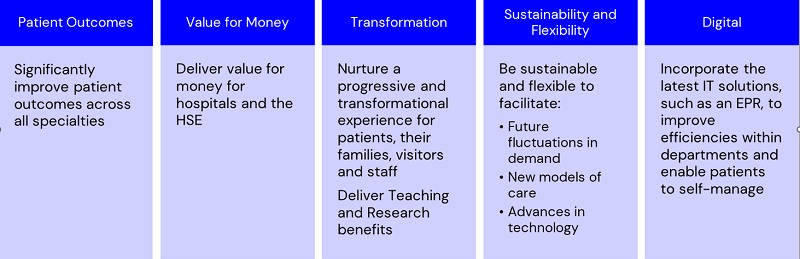

These objectives can then be categorised in a way which clearly defines the benefits and outputs of the programme, providing a useful tool to support staff and stakeholder communication and engagement.

For example, during a recent project we supported, objectives were categorised into five headline functional areas as shown below.

2. Defining the model of care

Politicians and the public rightly want shorter waiting lists. And, with a focus on greater efficiency and benchmarking against global best practice and performance, hospital sites can be made more responsive to maximise throughput.

The direction of all systems is integrated care.

A key objective of the Sláintecare transformation programme is ensuring treatment is provided in the right place at the right time.

This means consideration of all care pathways and a system change from single specialty, like outpatient consultations, to a focus on rehabilitation, post-72-hour medicine, and separating elective and emergency flows.

Concentration on therapy, diagnostics and treatment should lead to faster patient care, increased turnover, and improved outcomes – an opportunity we see specifically recognised in the Sláintecare Implementation Strategy and Action Plan (2021-23) and with the provision of additional elective care delivery capability in Cork, Dublin, and Galway as a stated Government policy objective.

3. Population modelling

Traditionally, hospitals performed specialty-based assessments of needs and added future demand modelling as revenue allocations permitted.

Future investment must reverse this approach, considering the needs of communities that hospitals as a whole serve and then seeking to identify and prioritise the projects required across associated clinical pathways.

This critical step can be the key to unlocking targeted savings and maximising the available value of budgets, while improving the patient experience.

For example, investment in rehabilitation could save 21% of the cost of an average over-80s inpatient episode. Similarly, there are savings in bed days from moving from elective to daycase, and daycase to OPD settings.

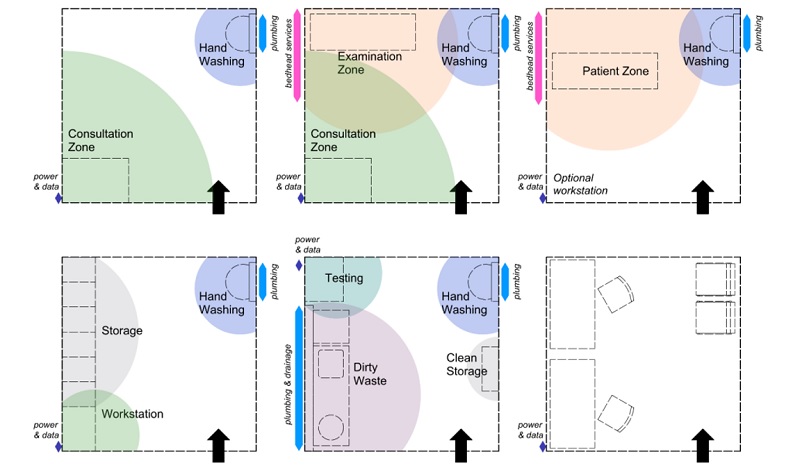

4. Design standardisation

In the face of major clinical and technological change, space design standardisation is a key opportunity for delivering not only long-term efficient floor plates, but also aiding a faster delivery programme for increasing hospital capacity.

Repeatable rooms and layouts are proven to be clinically safer, yet are not universally adopted, often due to the pressures of delivering shorter-term savings, with value engineering of rooms to the smallest-possible size based on bespoke requirements at a local level.

Yet this approach ignores the longer-term value opportunities which are generated by taking a standardised approach to design.

Standardised designs eliminate the need for duplication and condense the amount time required for stakeholder consultation, leaving hospitals to concentrate on maximising the effectiveness of local specialist areas.

In the face of major clinical and technological change, space design standardisation is a key opportunity for delivering not only long-term efficient floor plates, but also aiding a faster delivery programme for increasing hospital capacity

And the net benefit is significantly-reduced design costs, reduced pre-construction programmes, and significantly-minimised risk.

Of course, benefits extend into the construction phase, where we see standardisation as a key enabler to the use of Modern Methods of Construction and unlocking associated gains in time, cost, and quality.

The benefits continue during long-term occupation by providing long-term flexibility.

Rooms in hospital building might change their use 3-4 times in a 60-year term as clinical change and technology occurs.

So, applying standardised sizing to rooms in 8sq m increments up to 40sq m means the same room can be easily reconfigured to undertake a wide range of uses during its life.

Something as simple as a square consulting room can become several different facilities if kept to a uniform standard size – in the case below, 16 s qm2.

An example of room standardisation

5. Assembling a balanced team which is focused on revenue and workforce

Even though it is estimated that the operational costs of capital projects are a multiple of between 80-200 of the initial build cost, we continue to see a fixated focus on managing and reducing capital outlay, too often fuelling a need to make reactive design changes to achieve short-term savings.

Unsurprisingly, these savings often correspond with operational compromise and reduce efficiencies of operation, such as longer travelling distances for staff, or shared support spaces which aren’t reflective of workplace realities; a cost which then multiplies significantly over the lifetime of the asset.

We cannot lose sight of whole lifecycle cost. We must strategically invest capital to make buildings smarter and more operationally efficient, aligned with, and supported by, digital technologies and investment in diagnostics, to speed up and enhance both clinical delivery and the patient experience.

Referencing global best practice, we can look to ‘high-tech’ hospitals such as Sint Maarten in Belgium, Royal Adelaide Hospitals (2013), the new Humber River, and Helen Diller Parnassus Heights San Francisco to help shape and improve thinking.

These four examples all feature aspects of ‘Flow, Fabric and Footprint’ thinking which links patient benefit, staff welfare, risk management, innovative technologies for patient benefit and, crucially, environmental sustainability.

These ‘3Fs’ are becoming part of established global health digital understanding. More importantly perhaps, all demonstrate an ability to rethink traditional conventions to achieve greater productivity.

Even though it is estimated that the operational costs of capital projects are a multiple of between 80-200 of the initial build cost, we continue to see a fixated focus on managing and reducing capital outlay, too often fuelling a need to make reactive design changes to achieve short-term savings

Of course, standardisation appears here again as a key opportunity, and we see a growing body of standardised thinking when it comes to the design and implementation of digital technologies, illustrated well through our recent work with NHSX in England on a project that aims to achieve the adoption of some 19-21 standard digital systems being introduced in all future major projects.

Workforce is a finite resource. In healthcare systems globally, vacancy rates are forecast to reach unsustainable levels by 2030 and we are already seeing extreme shortages in areas like psychiatry, physicians, specialist surgery, and diagnostic posts.

Our plans for improving healthcare cannot modernise the delivery without being equally cognisant of the imperative to recruit and retain adequate levels of staff.

The projects we deliver must prove efficiency, avoid duplication, and be smarter and quicker, creating facilities where current and future staff want to work.

We will not be able to sustain a workforce of high-quality, experienced clinical professionals without providing them with adequate accommodation for both work and rest.

During the pandemic, we saw a common message from health systems that health clinics and hospitals had little room for attending to staff welfare, recovery, wellbeing, teaching, and research. And this must be addressed.

At times, we have seen capital and revenue plans developed in isolation, where the implications of a new facility on the clinical workforce planning and associated revenue costs are not fully understood.

There is little point in recruiting world-class surgeons if there are no theatre slots available, so, while challenging, greater joined-up system planning is needed.

6. Even better business cases

Projects must be affordable and deliverable.

Navigating the mandated business case process methodically and complying with the legislative requirements of the Public Spending Code is fraught with risk that must be considered and managed.

The process has sought to address historic issues with major capital projects, but still we can do even more to demonstrate how healthcare capital investments will truly deliver value for money.

We must ensure that the clinical demand is modelled 10-plus years ahead, including non-demographic growth; that it links to the clinical strategy; and that the Schedules of Accommodation correspond and link to design drawings.

We all understand inflation is topical, but using optimism bias as a place for short-term contingency is to misunderstand the context of risk across several workstreams and is no substitute for linking these steps together.

Too often, drawings are more than 5-10% over the requirements in the Schedule of Accommodation which has been used for the cost and programme plan.

Health leaders must expect clear funding streams, including revenue consequences, to be shared annually to help support a more-informed and inclusive project planning process and enabling them to move their development approaches from short-term and incremental to strategic and long-term

Again, we see the benefits that a standardised design approach might bring in reducing the risks of misalignment between the design, operation, workforce, and cost models.

Facilities management and information management technology strategies are often drafted in insufficient detail, leading to differing assumptions and the need for later compromises and trade-offs between operational, digital, and workforce requirements.

7. Standardised processes of communication

To improve efficiency and accountability, projects must employ a communications plan that is stakeholder focused and matches the design stages to provide regular – ideally monthly – updates to staff and local population.

Incorporating digital tools and social media platforms, including advanced visualisation tools like VR, can be a powerful way of communicating project aims and delivery – through a lengthy process, team personnel change, and collective memory dissipates, which is why recording and auditing of discussions, decisions, evidence and rationale is critical part of ongoing project communication, providing changing personnel with the context to maintain project momentum and ensure continued alignment with long-term strategic aims.

Simple, but not easy

Ellis said: “There are tensions in any healthcare system globally between national and local levels.

“The Sláintecare Implementation Strategy identifies capital investment as a critical enabler of the reforms proposed, including an increased focus on planning and management of capital development proposals.

“In return, health leaders must expect clear funding streams, including revenue consequences, to be shared annually to help support a more-informed and inclusive project planning process and enabling them to move their development approaches from short-term and incremental to strategic and long-term.

“But, what appears simple, is not always easy, and we must continue to work together to overcoming these challenges.

“The steps outlined offer a way for healthcare leaders and their teams to leverage proven techniques and evidence assessments to bring project stakeholders together, drive innovation, and redefine value in a way that will deliver long-term health benefits to the people of Ireland.”